Article by MATTHEW WELCH, excerpted from The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen, Paintings and Calligraphy by Japanese Masters by Audrey Yoshiko Seo with Stephen Addiss. (c) 1988 by Audrey Yoshiko Seo and Stephen Addiss, available for purchase from Amazon.com

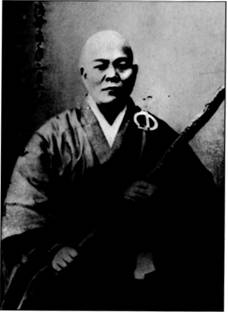

“IF I CANNOT BECOME A PRIEST of extraordinary accomplishment, I will not walk upon the earth,” vowed eighteen-year-old Nantenbō (Tōjū Zenchū) to his Zen Master.’ The impassioned spirit of this precocious young man was to burn brightly throughout his eighty-seven years. Not only did he rise through ecclesiastical ranks to an exalted position at one of the most prestigious Rinzai Zen monasteries in Japan, he was “a Zen priest of the people.”‘ In his determination to restore Zen to its former purity and brilliance, he emulated the severe methods of legendary Zen masters from the distant past. The thick staff of nandina he used to “encourage” disciples and frighten “false priests” resulted in a great deal of notoriety, giving him the nickname Nantenbō (nandina staff). He also published ten volumes of Zen commentaries, headed numerous Zen study groups and, by his own estimate, brushed over one hundred thousand calligraphies and paintings, which he freely gave away to anyone brave enough to ask. Certainly his efforts helped maintain Zen during Japan’s tumultuous modernization. By wielding the brush with unmitigated vigor, he also may have unwittingly exerted tremendous influence on twentieth-century “action” artists and avant-garde calligraphers.”

NANTENBŌ’S LIFE

Born to a samurai who served the Ogasawara daimyo in the port city of Karatsu, Nantenbō forfeited the privileges of his birthright in order to join the clergy. The death of his mother when he was only seven deeply troubled the youth, and, as he expressed later in life, he was determined “to understand the origins of life and death, to work for the salvation of sentient beings, and to pray for the repose of my mother’s soul.”5 At the age of eleven he joyfully submitted to the head-shaving ceremony for acolytes at the local temple of Yuko-ji. The Buddhist name he received, Zenchu (Complete Devotion), was to be a prophetic indication of his enduring commitment to Zen.

By eighteen, Nantenbō was ready for more rigorous Zen training. Acting on the suggestion of his teacher, he journeyed to Empuku-ji in Yawata, south of Kyoto. Acceptance into Empuku-ji, one of the three leading Rinzai sōdō in Japan, was a formalized procedure designed to test the resolve of aspiring monks. After two days and nights of prostrate begging to be admitted, Nantenbō underwent seven days of meditation in isolation facing a wall. Having completed these trials in an acceptable manner, he was formally admitted into the temple and assigned a place in the sōdō. Well known for its strictness, Empuku-ji seemed a cold and friendless place, even for the determined young monk. “When I entered the sōdō,” Nantenbō later recalled, “I stole a glance to the side and saw white eyes and hateful-looking faces-even now it makes me shudder.”

Despite the physical and mental rigors of life at Empuku-ji, Nantenbō flourished. On the very first night that he was accepted into the sōdō, he received the Mu koan from the priest Sekio Somin. This comes from a Chinese Zen story that a monk asked Joshu (Chinese: Chao-chou),’Does a dog have the Buddha-nature?” Despite the Buddhist belief that all beings have this nature, the Master answered, “Mu” (no, not). What might this mean? Night after night, Nantenbō courageously visited the Master in order to proffer his “answer,” only to be rebuffed. Undaunted, he redoubled his efforts. The evening meditation was not complete unless he had felt the force of the wooden keisaku stick across his back, encouraging him to greater depths of concentration.

Just before Sekio’s death in 1857, Nantenbō penetrated Mu. Over the next eight years, he devoted himself to koan practice, doggedly seeking out noted Masters upon whom he tested his understanding. He met with Satsumon Soon at Myoshin-ji and Sozan Genkyo at Empuku-ji. Traveling to Eifuku-ji in Fukuoka, he faced the notoriously inhospitable Ranno Bunjo, appropriately nicknamed “Demon Bunjo.” From the surly priest, Nantenbō received the training stick “thirty, sixty, one hundred twenty times.”‘

During the ceremonies commemorating the five hundredth anniversary of Myoshin-ji, Nantenbō met Razan Genma, head priest of Bairin-ji, a temple located in Kurume. Impressed with the youthful abbot, Nantenbō returned to his native Kyushu to study with him. After six years of strenuous effort, including meditating atop a board placed across the mouth of a well (if he fell asleep, he would plunge to his death), sleeping upright in the lotus position, and self-flagellation, Nantenbō managed to penetrate all but one of his koan.

Illumination of the final koan occurred when Nantenbō was twenty-six. According to his later account, as he traveled alone through the rugged terrain of Mount Aso, his path seemed to disappear into brambles and he was suddenly engulfed in an inexplicable darkness. At a loss, Nantenbō sat beneath a pine tree and began to meditate on the koan “Turtle-nosed Snake of South Mountain.”

Suddenly the surrounding grass was noisy with “zawa, zawa,” and as I opened my eyes there appeared in the thicket before me a great snake some fifteen feet long. It moved forward, and the grass and trees divided, making a path. It encircled the tree where I was sitting. A wind arose. No sooner had I seen the dreadful thing than it disappeared. The blackness into which I had been plunged was replaced with brilliant light, which shone through the mountains and valleys.’

Returning to Bairin-ji, Nantenbō immediately met with Razan, who was satisfied that his pupil had reached enlightenment. A few months later Razan recognized Nantenbō as his dharma heir with an inka(official certificate of spiritual attainment) and the priestly name Hakugaikutsu (White Cliff Cave).

Nantenbō’s accomplishment earned him a position as the head of Daijo-1i in Tokuyama Prefecture in 1869. He took his new duties to heart, earnestly training younger monks, ministering to a small lay following, and repairing temple buildings. Although he would eventually become a renowned Zen evangelist, at age thirty-one he recognized his own shortcomings, ruefully noting, “My lectures are like the drum used in sumo matches; they only summon spectators. They are not worth the dregs of the wine pot.”9 He persevered, however, delivering lectures at Daijo-ji and throughout Yamaguchi Prefecture. On these occasions Nantenbō admonished his audience toward strict Zen practice, refusing to offer salvation of the kind “bought and sold” by other sects.

It was during his travels in Kyushu in 1873 that Nantenbō discovered a large nandina bush growing beside a cow shed. From the owner, he learned that it was an ancient growth. While his companions waited by the roadside, Nantenbō pleaded with the farmer:

I have searched here and there, and this is a perfect dragon-quelling training stick. If this tree goes on this way, how long will it live? Someday it will wither and die…. In my hands, however, it will become an instrument of the dharma. This nandina will resound for countless generations. What do you say? Will you let me have it?10

The farmer gave in to the earnest monk’s request. Nantenbō cut a thick trunk, addressing the remaining stump: “I cannot live unless I make the most of your great death, you who have lived for two hundred years.”” When Nantenbō finally joined his waiting companions with stick in hand, they chided the zealous priest, playfully dubbing him “Nantenbō” (nandina staff). The appellation stuck, and the priest henceforth was known by this sobriquet. Inspired by his prized stick, Nantenbō embarked on a grand pilgrimage, visiting temples throughout Japan. According to Nantenbō’s later accounts, he challenged resident priests to dharma battles, beating them with his stick and chasing them from their temples if they lacked true understanding.

Nantenbō’s unshakable sense of right and wrong and fearless devotion to Zen often led to passionate disputes. On at least three occasions he even challenged the governing priests of Myoshin-ji, the head temple for his branch of the Rinzai sect. In 1879, amid great excitement over the building of a large new center for the study of Zen, Nantenbō was a vocal opponent. Echoing the ancient Chinese master Lin-chi’s rejection of scriptural pedantry, Nantenbō argued that monks should concern themselves with spiritual training, not scholarship. He recommended that the sect’s resources would be better spent by constructing a training hall. When his suggestion was rejected, Nantenbō’s disappointment spilled forth in acrid criticism: “an impregnable fortress is sometimes broken from within … priests such as these are worms in the body of a lion.””

On another occasion, the governing body at Myoshin-ji considered ranking temples according to their income. Priests from well-supported temples would receive high positions, while priests from humble temples, no matter how accomplished, would not be able to wear the exalted purple robes. There was widespread condemnation of the idea, and Nantenbō was chosen to represent thirty-one temples throughout Japan in delivering a petition of protest. Rebuffed at first, he sat resolutely in the garden of Myoshin-ji, vowing not to leave until the petition was accepted. In the face of the formidable priest’s determination, the Myoshin-ji authorities capitulated, and Nantenbō happily returned home.

Nantenbō’s most dramatic attempt at reforming Zen in Japan occurred in 1893. Convinced that many priests were undertrained or altogether fraudulent, he proposed that all high-ranking Zen clerics submit to a standardized series of koan in order to receive certification. In formulating the examination, Nantenbō consulted with six of the leading Zen Masters of the day, thus forcing the priests of Myoshin-ji to agree with the spirit of the proposal. Difficulty in carrying it out, and the discord that would arise as deficient priests were divested of their temples and rank, however, prompted Myoshin-ji to reject Nantenbō’s proposal. Although he felt betrayed and defeated, Nantenbō had succeeded in pointing out the widespread need for reform.

The unflinching determination of Nantenbō in the face of conflict attracted the attention of military leaders of the day. Shortly after becoming the head of the sōdō at Sokei-ji in Tokyo in 1885, Nantenbō met the famous swordsman and calligrapher Yamaoka Tesshu. The two men seem to have enjoyed a relationship of mutual respect and admiration until Tesshu’s death three years later. Tesshu invited Nantenbō to serve as Zen Master at a small temple in Utsunomiya that he was restoring. It was there, under Nantenbō’s instruction, that the famous generals Kodama Gentaro and Nogi Maresuke came for Zen training.

Nantenbō’s most prestigious appointment, in 1891 to the sprawling Zen complex of Zuigan-ji in Matsushima, ended a few years later amid a storm of controversy. While Nantenbō was away, an ancient statue of the famous warrior and patron of Zuigan-ji, Date Masamune, was accidentally damaged by a young acolyte. Although innocent, Nantenbō was blamed for the incident and ultimately resigned his position in an attempt to placate the outraged descendants of Masamune. Shocked and disheartened, Nantenbō secluded himself in the nearby dilapidated temple of Daibai-ji for two years. Far from being a period of bitter stagnation, however, it seems to have afforded Nantenbō a chance for quiet introspection and maturation. In a verse couched in imagery drawn from the name of the temple (Great Prunus) itself, Nantenbō suggested as much:

Great plum trees take twenty years to bear fruit.

In this place Nantenbō, too, ripens.

Two years later, Nantenbō’s first act after his reemergence from seclusion provides telling evidence of his new, more moderate approach to the propagation of Zen; he abandoned his cherished training stick. Reasoning that the formidable club might have frightened acolytes away from Zen practice, he locked it in the treasure house at Empuku-ji. Henceforth, although his Zen spirit remained fierce, he ceased the zealous rampages of his younger years.

In 1902, at the age of sixty-four, Nantenbō was asked by Myoshin-ji to take control of Kaisei-ji in Nishinomiya. A medium-size temple with a venerable tradition, Kaisei-ji was to be Nantenbō’s home for the next twenty-three years until his death in 1925. Perhaps because of his former notoriety, Nantenbō immediately attracted a sizable following. His reputation was bolstered even further when, in 1908, he was designated as the 586th Exalted Master of the main temple of Myoshin-ji. Largely ceremonial, the honor nevertheless confirmed Nantenbō’s high standing among his contemporaries.

NANTENBŌ’S ART

Nantenbō first began to produce painting and calligraphy in his early fifties during his brief period at Zuigan-ji. This late date is not unusual, given the traditional Zen rejection of artistic cultivation among its clerics. In the past, harsh judgments were levied against monks who strayed from their prescribed routines. The Zen Master Muso Soseki (1275-13S1), for example, once disparaged monks who occupied their time composing poetry:

Then there are those, who besotted with poetry, conceive of their vocation as a literary one-these are shaven-headed laymen, not worthy of inclusion in even the lowest grade. Nay, they are stuffed with food and stupid with sleep, vagrant time-passers I called frocked bums! The ancients had another name for them: “robed ricebags.” They are not monks, and certainly no disciples of mine.”

Similar criticisms have been aimed at those who neglect their spiritual practice while perfecting brush techniques. Nevertheless, there is also a seemingly contradictory tradition in Japan of collecting and admiring the calligraphy of high-ranking Rinzai Zen priests. Termed bokuseki, or “traces of ink,” such works were thought to resonate not only with the spirituality of the priest who wrote them, but with that of his teacher and his teacher’s teacher, all the way back to Daruma himself.

In this light, it is reasonable that Nantenbō, as the newly appointed head of Zuigan-ji, complied with requests for samples of his calligraphy in spite of the fact that he had little previous experience with brush and ink beyond the rudiments of writing. Indeed, the earliest datable works of painting and calligraphy by Nantenbō are signed “one hundred twenty-fourth generation [of Zen abbots] at Matsushima, Nantenbō,” thus indicating his historic position at that temple.

While Nantenbō was compelled to take up the brush by virtue of his new position, he seems to have taken readily to it. His own comments are refreshingly devoid of aesthetic or religious posturing, expressing instead a certain workaday quality in his approach:

My writing is quite fast, as I am not concerned with the rules of calligraphy or whether it is good or bad. I write a page a minute, so it is nothing for me to write sixty sheets in an hour.”

Despite this astonishing rate of production, there were times when Nantenbō was beleaguered with requests for works by his hand:

I don’t know of any magical quality about my bokuseki, but recently everywhere I go I am asked again and again to write. It is as i f I have become a professional calligrapher.

Ultimately Nantenbō’s use of the brush was a form of Zen practice. Like any activity performed by Zen adherents, it was an opportunity for concerted concentration. This concept was not a new one. At the heart of communal, monastic existence was the necessity of carrying on daily activities in addition to periods of seated meditation. Implicit in the ideographic compound gyojuzaga (walking, standing, sitting, lying) is the idea that all activities should be performed with a Zen spirit.” Nantenbō reveals this attitude in a passage from his autobiography:

The reason for not speaking while writing a large character is that the character will “die” unless it is written in one breath. One should magnify one’s spirit and write without letting this magnified spirit escape. The character will die unless it is written using the hara [literally, gut, here suggesting the center of one’s spirit].

For his calligraphy, Nantenbō drew heavily upon existing Zen literature. In 1917, his seventy-ninth year by Japanese count, he wrote three boldly dramatic characters for Mumonkan in hanging scroll format. Literally “no gate barrier” or “gateless gate,” this calligraphy simultaneously refers to the classic koan anthology compiled in 1228 by the monk Wu-men (Munlon) and to the nature of Zen itself, that is, an ineffable state that is at once “gateless,” and yet not easily entered because of humankind’s deluded manner of thinking.

Typical of Nantenbō’s calligraphic style are the blunt beginnings and endings of each stroke, almost as if he were using a worn, old brush. The strokes are thick and meaty, and given further strength by dense ink tonalities. Eschewing supple smoothness and precisely shaped strokes associated with professional calligraphers, Nantenbō cultivated a certain coarseness and imperfection. The sweeping, abbreviated form of the character for mon ( gate), for example, arches irregularly with bumps and ragged edges. By allowing the brush to go dry, each twist and turn is given accentuated texture. For all its masculine bravura, however, Nantenbō’s Mumonkan is admirably composed. The open, airy character of mon contrasts nicely with the compact, complicated forms of Mu ( no, not) and kan ( barrier), above and below it.

When Nantenbō painted themes that lack such an obvious Zen connection, his accompanying inscriptions often suggest underlying Zen interpretations. The subject of crows is represented among the vast number of paintings by Nantenbō by a single known example painted in 1920 at the age of eighty-two. Within the confines of a narrow hanging scroll, Nantenbō painted eighteen crows flying chaotically about. Each crow is the result of as little as two or three strokes of the brush. Nantenbō painted the splay of wing feathers by holding the brush diagonally to the paper. Also, by loading his brush with both dense and diluted ink, he was able to impart a certain depth and variation to the shape of each bird. Nevertheless, the overall technique is more expressive than descriptive. Indeed, certain shapes would not be readable as birds at all, if not part of a greater conceptual whole. The extreme brevity in which the crows were rendered, however, ultimately contributes to a sense of movement, as if the startled flock occupies the atmospheric space just before the viewer. Nantenbō’s six-character inscription takes the form of a rhetorical question, akin to a Zen koan:

Why are these crows flying about in the sky?

In Zen, the dualist distinction inherent in the question “Why?” is rejected; instead, there is an unquestioning acceptance of the nature of existence. In this case, the cause of the crows’ commotion is irrelevant; there is just “flying.” In this light, Nantenbō’s choice of crows is particularly appropriate: their black feathers suggest somber-robed monks. The raucous, erratic behavior of the agitated birds serves as a metaphor, perhaps, of the unsettled, grasping minds of Zen acolytes searching for enlightenment beyond themselves.

Ink on fan paper, 40.5 x 24 cm.

Genshin Collection

On some occasions, Nantenbō’s choice of a painting subject was influenced by a secular story or parable. His images of spirited horses, for example, were inspired by an ancient Chinese anecdote, as suggested by a fan painting dated age eighty-four with Nantenbō’s inscription:

The myriad concerns of man

are like old man Saio’s horse

The original account, attributed to the legendary Chinese philosopher Huai Nan-tzu, relates how old man Saio was undisturbed when his horse ran away, saying that somehow, some good would come of his loss. After several months the horse returned, leading a prize stallion. Much to everyone’s surprise, however, Saio did not rejoice. Within a short time, his son fell off the horse and broke his leg. Once again, however, Saio accepted his misfortune with equanimity. Because he was lame, the old man’s son avoided conscription in the army. The full extent of the old man’s wisdom was made clear when his neighbors’ sons failed to return from battle.

Nantenbō’s method of painting horses is spontaneous and intuitive. With a few thin strokes he indicates the beast’s muzzle, nostrils, and jawbone, and several dry, horizontal dashes serve to convey the flying mane. The forelegs are drawn with a stroke that abruptly shifts direction, effectively suggesting the sharp bend of the racing animal’s knees. The hind legs are not shown; they exist just beyond the pictorial surface. The tail is a single dry stroke that swings upward. The absence of a ground plane, sketchily indicated in other paintings, further suggests the high-speed flight of the horse. Here, on the format of a fan, he has painted a horse that would move as the recipient of the painting waved the fan in front of his face.

In painting this theme, Nantenbō may not have been trying to convey any special Zen meaning. The historically auspicious nature of horses, coupled with the hopeful story of Saio’s horse, may have simply served to encourage lay followers who had fallen on hard times. If so, such paintings demonstrate Nantenbō’s position as a compassionate community elder.

twelve panel screen)

A sympathetic attitude toward his lay following may have been the impetus for Nantenbō to write the iroha syllabary across twelve panels of a pair of folding screens. The iroha is a set arrangement of forty-seven simplified Chinese characters used for their phonetic value in order to record spoken Japanese. Until recently, Japanese children memorized this syllabary by using as a mnemonic a poem, legendarily attributed to the great ninth-century Shingon priest Kukai, in which the syllables form the words:

Iro wa niedo

Chirinuru o

Waga yo tare zo

Tsune naran

Kyo koete

Asaki yume mi-ji

Ei mo sezu

Though the colors [of autumn flowers]

Are bright,

They fade away.

Who in this world of ours

May continue forever?

Crossing today the boundaries of the physical world,

No more shallow dreams or intoxication.”

While not specific to Zen doctrine, the verse-written across twelve panels-clearly represents the Buddhist view of life on earth as sorrowful and transitory. It also serves as a reminder to attend to one’s salvation, the raison d’etre of all Buddhist priests. Nantenbō’s bold brush lends power to the simplified kana (Japanese phonetic) shapes of the iroha. The sheer size of the object transforms the familiar children’s poem into a startling mandate. The characters are bold and substantial, defined by thick strokes of relatively even width. The interplay of velvety black ink and “flying white” creates a sense of movement and depth. Like the earnest letters of young children, Nantenbō’s kana are devoid of refinement or elegance. Instead, the ragged edges and frayed endings of strokes convey a raw grittiness that is at once naive and powerful.

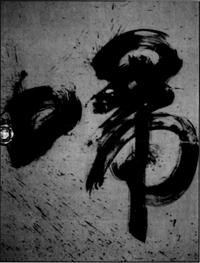

Ink on paper, 168 x 103 cm.

Kaisei-ji

Nantenbō s most famous work on a monumental scale remains in the collection of the Kaisei-ji. Each character of an eight-character couplet was written on a full-size fusuma sliding door, one per door. When installed within the bays of opposing sides of the main altar, they create an unsettling environment of great power and violent movement. The couplet, evoking the ominous sounds of powerful beasts, well agrees with the wild, untamed spirit of Nantenbō’s calligraphy:

The dragon cries at dusk,

The tiger roars at dawn

In many cases the characters seem ill-formed, probably owing to the difficulties of working on so great a scale. What seems to have been of paramount concern to Nantenbō was not the proper rendering of the characters, but that they transcend their two-dimensional nature and convey the strength and movement of the brush. Nantenbō accomplished this by heavily loading his oversized brush, slightly pinching the tip to momentarily stop the flow of ink out of its bristles, and then with great gusto forcefully hitting the paper. The result was a great splash of ink beginning the initial stroke of each character-a clear record of the drama and potency of the moment.

The ambitious scale and trademark splash of this work ultimately influenced later calligraphers. The works of Kanshu Sojun and Kasumi Bunsho, both direct pupils of Nantenbō, clearly reflect his dynamic style. The celebrated contemporary calligrapher Morita Shiryu credits Nantenbō’s work as having exerted a formative influence on his style.” And Yoshihara Jiro, founder of the Gutai group of avant-garde artists in the 1950″ and ‘6os, frequently took fellow artists to Kaisei-ji to see Nantenbō’s powerful sliding doors. Gutai members rejected traditional painting methods, which they believed dampened intuitive creativity by being overly intellectual. Instead, they advocated more direct, experiential methods of using material to reflect the physical, emotional, and spiritual moment of creation. This approach harkens back to Nantenbō’s insistence on Zen concentration and the use of hara.

The fact that the majority of Nantenbō’s images were painted during the final decade of his life is a testament to his continuing vitality. Ultimately he seems to have developed a basic repertoire of about sixteen subjects, which he painted again and again with great gusto. In doing so, Nantenbō followed in the footsteps of other Zen Masters, particularly of the Edo period (16oo-i868), for whom Zen painting was a significant mode of expression. Their simple pictures were a convenient and vivid means of making abstruse Zen principles more accessible to lay people.’ The spontaneity, technical naivete, and humble materials were at least partially the result of Zen priests’ avowedly amateur status. As with calligraphy, it was inappropriate for anyone but high-ranking, enlightened Masters to produce Zen paintings.

Imaginary portraits of the First Zen Patriarch, Bodhidharma, called Daruma in Japanese, are the most frequently encountered of all Zen-related subjects. All Zen Buddhists trace the existence of their doctrine to this Indian sage who, according to legend, left his homeland in the late fifth or early sixth century in order to propagate his brand of Buddhism in China. Daruma stressed meditation above all other methods of achieving enlightenment. In fact, it is said that he accomplished the astonishing feat of sitting in meditation ceaselessly for nine years while facing a wall at Shaolin temple on Mount Sung.

Iron glaze on ceramic, 7.4 cm. tall

Gubutsu-an

Nantenbō began to produce bust-portraits of Daruma in his early seventies. Many of these are boldly rendered, large-scale images. An unusual example, however, was painted in glaze when he was seventy-five on a small teabowl. Rendered in iron-oxide on cream-colored clay, the composition was completed in just a few strokes. The furrowed brow of the First Patriarch is suggested by two parallel lines. The eyebrows, beard, and hair are indicated by a series of rapidly applied dabs. The mouth is a single downward arch, and the eyes are nearly round circles with black dots for pupils. A single stroke indicates Daruma’s robe as it falls from his left shoulder across his chest, covering his hands. The overall effect is charmingly simple and humorous. With an extreme economy of means and deliberate naivete, Nantenbō effectively conveyed the two characteristics most associated with the First Patriarch: his devotion to meditation, suggested by his wide-eyed stare, and his fierce determination, conveyed by his firmly set mouth. Daruma’s portrait on a teabowl also recalls some of the more fantastic legends associated with the revered sage’s life. Unable to keep his eyes open during his protracted meditation at Shaolin temple, lie is said to have ripped off his eyelids in frustration; tea plants sprang spontaneously from the ground where the eyelids fell, thus beginning the custom in monasteries of drinking tea to prevent drowsiness. Such stories make Nantenbō’s use of a teabowl for a portrait of Daruma altogether fitting.

Nantenbō inscribed the teabowl with a short, four-character quote attributed to Daruma himself. According to tradition, this was Daruma’s pointed response when Emperor Wu (502-550) of the Liang dynasty asked him to recite the sacred truth’s first principle:

Vast emptiness; nothing sacred

In addition to frontal portraits, Nantenbō also painted a number of images showing Daruma seated in meditation as seen from behind the sage. Long favored as a painting theme by Zen priests, these images are identified as “menpeki Daruma” or “wall-facing Daruma,” referring to the ancient sage’s nine years of meditation while facing a wall. As early as the fourteenth century in Japan, Zen artists playfully depicted the sage’s silhouette by means of a single, meandering outline in a technique known as ippitsuga (one-stroke painting). Later priests, including Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1769) and the Shingon monk Jiun Sonia (1781-1804), produced their own variations on this theme. Hakuin’s men peki paintings are characterized by two or three thick, even strokes that fluidly outline the shape of the First Patriarch.” Jiun, on the other hand, used a dry brush and angular strokes to create an architectonic Daruma.26 Both men, however, clearly indicated the sage’s head and the shoulders and the splay of his robe.

Ink on paper, 146.3 x 34.5 cm.

Murray Smith Collection,

Promised Gift to the

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Nantenbō’s conception of the menpeki theme is even more abbreviated than those of his predecessors. By eliminating the distinction between the head and shoulders, Nantenbō further distilled the silhouette of the First Patriarch. A simple, inverted U-shape is used to connote Daruma’s body, and a horizontal ellipse is meant to imply his knees beneath monkish robes. Nantenbō’s method of rendering these elements, however, is so geometric as to be unreadable as a cloaked figure. In a final denial of pictorial volume, Nantenbō impressed his seals within the outline, thus assertively calling attention to the surface of the paper. The abstract nature of the figure, however, only accentuates the quality of the ink, applied in a single sweeping stroke of great energy.

Was Nantenbō simply inept at pictorial representation, or was he a visionary who pushed Zen painting further into a realm of dynamic epigraphs and emblems? The inscription on his menpekipainting offers a playful acknowledgment of the image’s ambiguous nature:

The shape of Daruma facing the wall–

is it like a melon or an eggplant

from the fields of Hachiman in Yamashiro?

It is likely, in fact, that Nantenbō intentionally challenges people’s rigid preconceptions about the nature of Daruma. In his autobiography he notes that while he receives many requests for paintings of Daruma, his images are often criticized for looking like owls or octopi. “Very interesting,” the old priest observes. “People talk as if they have seen Daruma, but who has seen the original Daruma?”

Another traditional theme frequently painted by Chinese and Japanese Zen priests and literati artists is the ox or water buffalo. The gentle nature of these huge, lumbering beasts embodied their bucolic existence, far removed from the din and turmoil associated with life in the cities. In Zen literature, the progressively harmonious relationship between a herdsboy and his ox served as a metaphor for the quest for enlightenment. Composing Ten Oxherding Songs, sets of poems about each successive stage of spiritual awareness, became popular among Chinese monks during the Southern Sung dynasty.28 Illustrated versions imported from China that are listed in the inventories of the shogunal collections helped to establish this theme in Japan.” Early Japanese versions closely follow Chinese prototypes; the ox is rendered in soft washes, fine texturing strokes, and occasional descriptive outlines, and the oxherder and his beast are usually pictured within an abbreviated landscape setting.

Ink on paper, 135 x 33.6 cm.

Oliver T. and Yuki Behr Collection

In contrast, Nantenbō created a drastically distilled composition. The great bulk of the ox is defined by a single outline. Two dabs of ink indicate horns, and a thin, trailing stroke is used to connote a tail. A few horizontal strokes punctuated with vertical dashes indicate the grassy ground. The simple, triangular composition is balanced, imparting a sense of tranquillity to the already staid form of the recumbent ox. In the inscription Nantenbō likens himself to the old ox, thus transforming the painting into a form of self-portrait:

Nantenbō–

when the bull is tamed

it becomes peaceful

STAFF

Ink on paper, 148.2 x 47.3 cm.

Private Collection

Nantenbō clearly delighted in the expressive potential of abbreviated imagery that becomes self-portraiture.” He rendered his favorite subject, his Zen training stick of nandina, by striking the paper with a heavily loaded brush and then dragging it downward to indicate the length of the stick. The initial explosion of ink, with spatters in all directions, is vivid evidence of the physicality of his approach. To this single stroke Nantenbō roughly rendered the cord and tassels attached to the stick in contrastingly pale ink tonalities. The overall result is an image that vibrates with energy, conveying the vigor of Nantenbō’s technique rather than pictographic description. The potent ferocity of Nantenbō’s images of training sticks is echoed by his inscription:

If you speak, Nantenbō

If you don’t speak, Nanten[bo]

In other words, you will receive a blow from the nandina stick (and also Nantenbō himself) whether or not you are able to respond to Nantenbō’s koan. This inscription echoes a terse statement attributed to the Chinese priest Te-shan: “If you speak, thirty blows; if you don’t speak, thirty blows.” This seemingly illogical and harsh message from master to disciple exemplifies a pivotal concept in Zen training: after experiencing an initial awakening, a Zen practitioner must not become complacent. This is why it is said that someone who has reached enlightenment never clings to it but moves on” In the same manner, a responsible Master continues to prod his disciples onward, using every means available, including a few sharp blows with a stick.

Symbolic shapes and gestures have long been a part of Buddhist practice and worship. In Zen Buddhism, ensō (Zen circles) were first used by Chinese Masters during the Tang dynasty to symbolize perfection. The Master Nan-yueh Huai-jang (677-744) used circular figures to symbolize the nature of the enlightened consciousness or the `original countenance before birth.””‘ And several accounts in the Hekiganroku,(Blue Cliff Record), an eleventh-century compilation of koan, record the use of circles-drawn in the air, scratched in the earth, or written on paper-during encounters between pupils and Zen masters. It is not surprising that Nantenbō, with his demonstrated penchant for elliptical imagery, also painted ensō. What is unexpected is his subdued approach. Rather than an explosive splash of ink followed by a rapidly brushed circle, Nantenbō’s ensō inevitably exhibit the bumps and imperfections of a brush dragged slowly across paper, responding to the priest’s every pulse and tremor. Nantenbō also altered his composition to best accord with the meaning of the inscription. In works where he likens the ensō to the full moon, the circle floats high above the inscription.

Ink on paper, 20.9 x 17.8 cm. Hosei-an Collection

In a charmingly small example datable to his eighty-fourth year (PLATE 11), Nantenbō purposefully placed his inscription within the circle:

Born within the ensō of the world

the human heart must also

become an ensō

Nantenbō playfully enlivened his inscription by using small circles to indicate the words circle and round, thus drawing two ensō within the larger ensō.

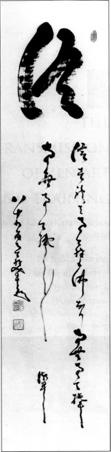

Ink on paper, 133.7 x 33 cm.

Private Collection

In spite of his crusty personality, it is clear that Nantenbō never lacked compassion or humor. On a number of occasions he even acquiesced to requests for non-Zen phrases, including the mantra of the Jodo (Pure Land) sect of Buddhism: Namu Amida Butsu (Praise to Amida Buddha). Earnest recitation of this verse, according to Pure Land beliefs, would ensure rebirth in Amida’s Western Paradise. Such deference to the saving grace of Amida (tariki, other-power) is antithetical to the Zen concept of enlightenment through one’s own effort (jiriki, self power). Nevertheless, many Zen priests demonstrated tolerance toward lay followers who found comfort in reciting the name of Amida. Recognizing the efficacy of such religious belief, Nantenbō wrote the character shin (faith) at the top of a hanging scroll. In an attempt to remind us of the pervasiveness of the Buddha-nature, however, he playfully added the following inscription, substituting his own name for that of Amida:

Faith

If you have faith, then Nantenbō is also Buddha

Namu Nantenbō, namu Nantenbō, namu Nantenbō…

With a limited repertoire and humble materials befitting his position as a Zen priest, Nantenbō exercised remarkable creativity and freedom. He cultivated a rough, brusque quality in his calligraphy, and an equally unpolished style for his imagery. His vigorous approach and complete rejection of pictorial artifice pushed the boundaries of abstraction, surpassing even the abbreviated images of his immediate predecessors. In doing so, Nantenbō transcended his Edo-period roots and firmly established Zen expression within a twentieth-century context. And yet it is unlikely that Nantenbō purposefully set out to further the boundaries of artistic expression. As a dedicated priest, he strove to propagate Zen and to maintain the high standards of past Masters. His marvelous works of painting and calligraphy are only the residual remains of his fierce Zen spirit.